4.10.2018 | Corrine Armistead

I am Corrine Armistead, Earth Economics’ GIS Lead. My interest in understanding natural systems and their interactions with economies led me to Earth Economics. Specifically, I am drawn to the possibilities of informing our work through maps and am currently pursuing a master’s degree in Geospatial Technologies at the University of Washington, Tacoma. I’ll be stopping by this blog with tidbits about our current work, intriguing/fun graphics, as well as general discussions about the wonderful world of maps.

Corrine at Arches National Park, Utah.

How do maps and spatial analysis fit into Earth Economics’ mission of quantifying and valuing the benefits of nature? Or, asked another way, how are economic valuations of natural capital linked to mapping? For me, two themes emerge to capture the role mapping plays in applications of ecological economics—simplifying a complex world and illuminating relationships.

All maps are simplified representations of our world; we cannot possibly include everything on a map. Similarly, even with rapid improvements in data collection and storage techniques, the spatial data underlying maps captures only pieces of complex systems. Using topographic, climatic, hydrologic, and imagery data, the earth is increasingly classified into ecosystems. Defining these systems—relationships among species groups and their environments—creates categories and common language. With these categories in hand, mapping which ecosystems are present where is a critical first step towards ascribing value to nature.

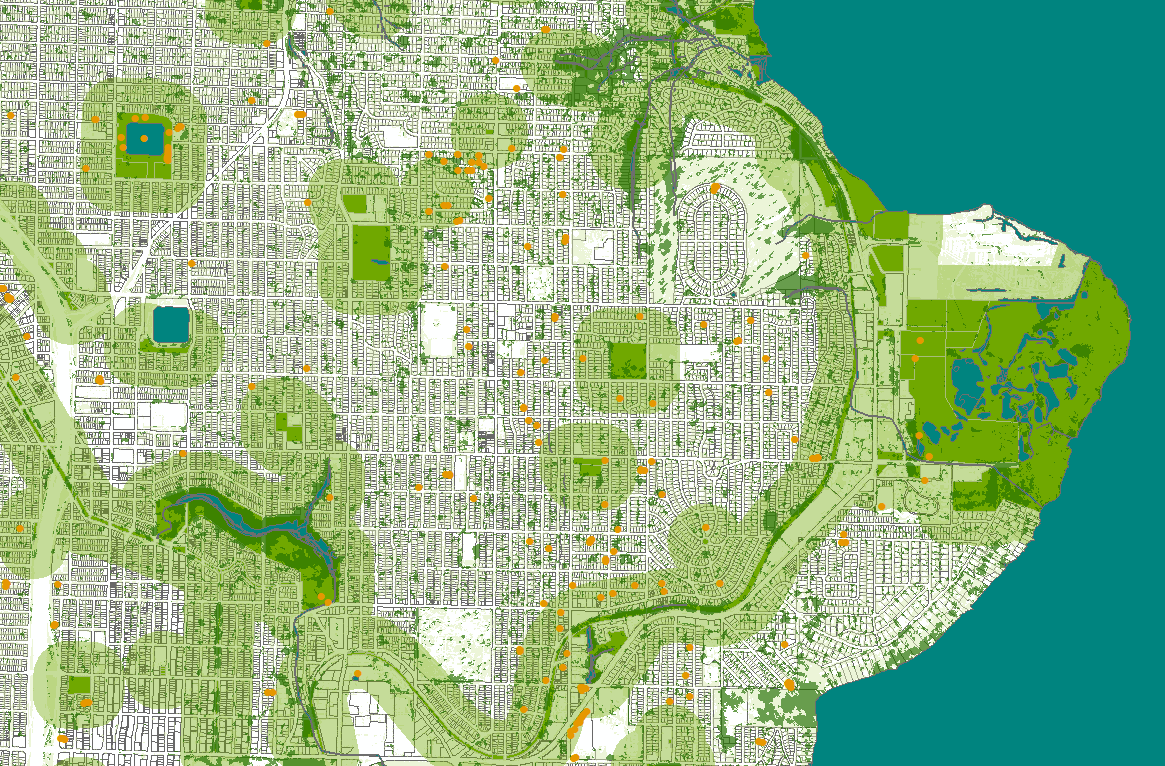

One view of greenspace in Seattle, with Magnuson Park in the upper right.

I can create a mental picture of a wetland, forest, desert, urban, or other general type of ecosystem. Less clear, however, are the entanglements of those physical systems with my individual and overall human well-being. Exploring these relationships is the work of ecological economics.

Spatial analysis helps discover links across space and time—between ecosystems, between communities and ecosystems, and between these interactions and larger scale processes. Of valuation articles published in the journals of Ecological Economics and Ecosystem Services so far this year, 70 percent directly incorporate spatial analysis into their methods. No doubt others also use geographic information systems (GIS) technologies in phases of study design, survey administration, or data analysis.

Whether revealing relationships among coastal storm surges, wetlands, and property damage, or the distances people are willing to travel to visit public recreation lands, spatial data analysis adds richness to models that value ecosystems. As data collection and analysis technologies continue to improve, I look forward to increasingly complex spatial representations of our world along with new opportunities to leverage this data towards a better understanding of relationships with and values of nature.

Corrine is attending the American Association of Geographers’ Conference this week in New Orleans. She will be presenting Wednesday, April 11, on framing urban green infrastructure through ecosystem services, specifically the inclusion and visualization of cultural ecosystem services. She is excited to learn from and connect with the diverse array of geographers attending, while saving time to eat as much jambalaya as possible.